Textile Trailblazer: The Art and Craft of Marian Clayden

Anyone who was lucky enough to have visited London’s Fashion and Textile Museum in the Spring of 2016 will appreciate the art and craft of Marian Clayden, exhibited in this breathtaking show shortly following her death in 2015. I’m surprised such a trailblazer in the world of textile art still remains relatively unheard of in fashion and design circles.

Marian Clayden was born in Preston, England, in 1937, and spent her early career teaching primary school children in Nottingham and Chorley. She later emigrated to Australia, before moving to California in 1967, where she established her textile design studio in Los Gatos. It was here that, due to an allergic reaction to textile dyes, she was forced to hire assistants to help with this process, which may be one of the reasons she was able to transition from textile art to limited edition clothing design, setting up Clayden Inc. in 1981. Clayden’s luxurious crinkled velvet designs have since seen her likened to Mariano Fortuny. Yet how did an expert in tie-dye progress to making clothes for Barbara Streisand, and Oprah Winfrey?

The concept of textile art was born out of the Arts and Crafts movement in the mid-19th century, and ‘fiber art’ remained a niche discipline in the USA until the 1940s. By the 1960s and ‘70s, however, Northern California had become a “hot bed of the textile arts,” and the Japanese born artist, Yoshiko Wada, was important for introducing the region - and Clayden in particular - to Japanese dyeing techniques, especially shibori, through her classes.

Clayden’s career also took a huge step forward when she met Nancy Potts, a producer, set and costume designer, who ended up commissioning Marian to produce the textiles for nine tours of the musical, Hair. She later collaborated with talented designers and fashion influencers the world over, including Ben Compton, Mary McFadden, Rudi Gernreich and Cecil Beaton.

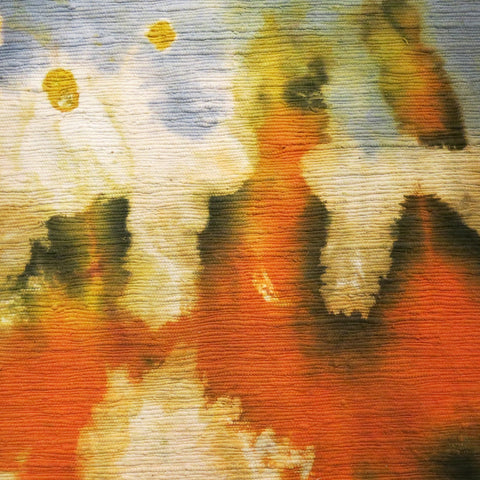

Following a number of high profile exhibitions of her work, Clayden continued to experiment further with techniques of burning, brush discharging and space-dying, where fibres are dyed instead of the yarns, as in Ikat. She spent a year in mid-'70s Iran, practising her craft, and gaining further inspiration, as well as time in India and Asia, evident in her love of vibrant colour.

Clayden wanted her work to be accessible to others, claiming, “I’m not just an artist doing this stuff that says ‘Do Not Touch’… it’s more immediate, it hangs in your wardrobe and it lives a real life.” Like the artist and designer Sonia Delaunay, Clayden made no distinction between work for the wall and the work for the body, stating in a 1996 interview that she was, “most satisfied when people get as much pleasure from that garment sitting in their wardrobe as from a piece of good art on the wall.”

By 1988, Clayden was producing four collections a year, primarily from a family run business, with production close to her California home. In the foreword to a catalogue from her exhibition The Dyer’s Hand, she says, “The real thrill of clothing design was making a successful combination of all the elements – body, style, fabric, drape, dyeing, and how it moves when worn – so as to create a garment that makes the wearer feel she is enclosed in something as valuable to her as a work of art.”

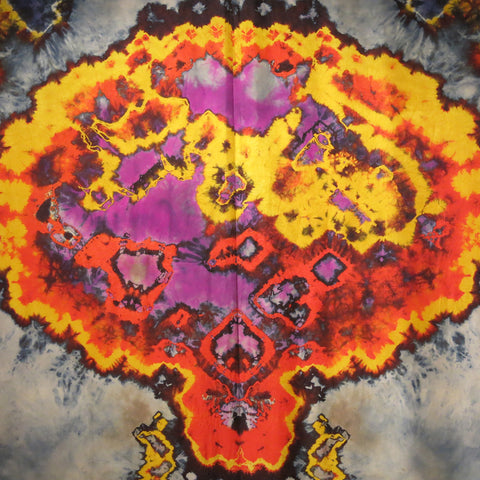

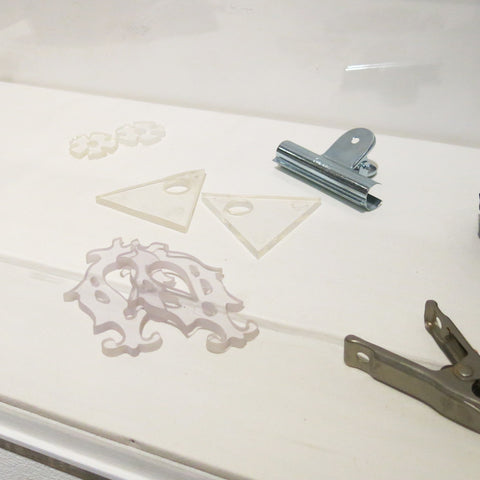

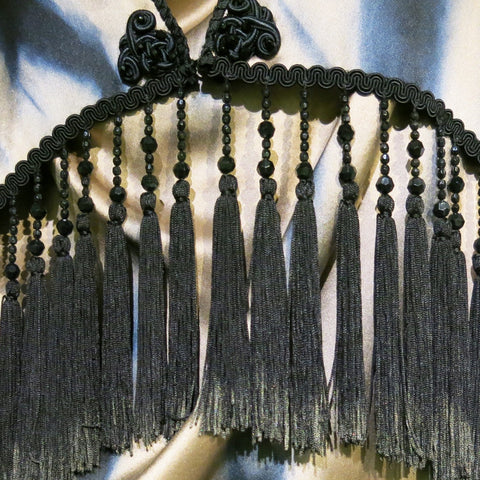

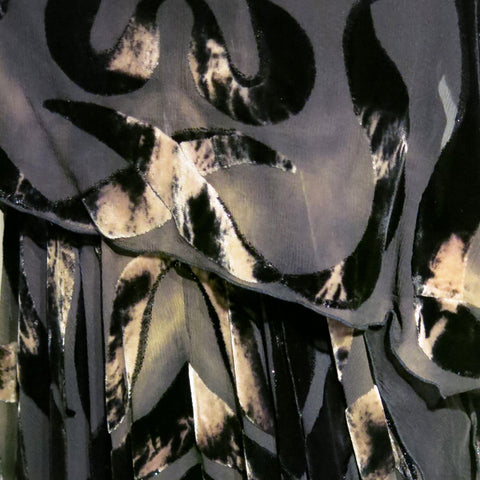

Clayden’s unique garment designs used folding, dipping, clamping, and discharging, as well as new, less orthodox, ways of decorating cloth, like the print motif she created by burning fabric in a sandwich toaster. Her use of cut velvet panels, produced in France, led to the increasing popularity of her designs - and the emergence of the fashion for devoré - in the 1990s. Her collections were sold in Niemen Marcus and Saks Fifth Avenue – and worn by the likes of Diana Ross, Cher, Elizabeth Taylor, Whitney Houston and Meryl Streep.

Clayden soaked up inspiration from her travels around the world, and in 1992 was invited by Aid to Artisans to work alongside Hungarian felt makers, creating what became an award winning set of designs that influenced the future evolution of her style. In advance of their time, her creations employed clever draping and geometric elements, intended to waste little or no fabric. Despite changing her textiles and colours seasonally, Clayden often kept certain shapes in production for years. The Twilight Jacket featured in ShopCurious’s Arts and Crafts 2.0 collection is just one example of her contribution to slow fashion and textiles, being eminently wearable and stylish to this day.

Photographs shown here were taken at the Fashion and Textile Museum’s Marian Clayden exhibition, Art Textiles in 2016.

We have an original wall hanging like the one pictured above, the different colored tapestry.